Today, I did a tasting comparison of four Wuyi Rougui teas. They were all made by the same master, using the same process, but each comes from a different part of Wuyi Mountain.

One is from the core Wuyi Rock Tea region (the Three Pits and Two Streams area), one is from the Zhengyan area, one is from the Banyan area, and the last one is from the Zhoucha area.

What is Wuyi Rock Tea?

You might be wondering: if they’re all Wuyi Rock Teas, what’s the difference between these regions? Well, before diving into that, let me give you a quick intro to what Wuyi Rock Tea is and how it’s categorized.

According to the national standards for Wuyi Rock Tea, it’s defined as tea made from specific tea tree varieties, grown within Wuyi Mountain’s unique natural ecosystem, and processed using traditional techniques. This tea has a distinctive “Yan Yun” (rock aroma and floral fragrance) quality.

For tea to be considered Wuyi Rock Tea, it must meet these criteria:

- Grown in Wuyi Mountain’s 2798-square-kilometer area.

- Made using the traditional processing method (shaped into twisted leaves).

- Has the characteristic Yan Yun quality.

It is a protected geographical indication product in China.

Differences Between Tea Areas

Now, how are these different Wuyi tea areas (core Zhengyan, Zhengyan, Banyan, and Zhoucha) distinguished?

- Core Zhengyan: Tea grown in the Three Pits and Two Streams region (including Huiyuan Pit, Niulankeng, Daoshui Pit, Liuxiangjian, and Wuyuanjian).

- Zhengyan: Tea grown within the scenic area of Wuyi Mountain.

- Banyan: Tea grown in the surrounding hills and semi-hilly areas.

- Zhoucha: Tea grown on the plains and mountainous areas near the two rivers of Wuyi Mountain.

The main difference between these areas, aside from their geographical range, is the soil type.

The Zhengyan region has volcanic rock, red sandstone, and shale, while the Banyan region’s soil contains a mix of half-weathered rock and gravel. Zhoucha has alluvial soil from the three streams (Chongyang, Huangbai, and Jiuqu) near the Wuyi Mountain.

Charcoal Roasting vs. Electric Roasting

All of these teas have been traditionally charcoal roasted, not modern high-temperature baked. So how can we tell if it’s charcoal roasting or electric roasting?

- Dry leaf color: If the dry tea leaves have a slightly grayish or whitish look, that’s usually a sign of charcoal roasting. Electric roasting, on the other hand, tends to preserve a greener color, without the noticeable white coating.

- Taste: Charcoal roasted teas often have a smoky, fire-like taste.

Why does it matter whether it’s charcoal roasted or electric roasted? Traditional Wuyi Oolongs are charcoal roasted, which requires more skill and experience.

Electric roasting is quicker but doesn’t infuse the same depth of flavor. Charcoal roasting imparts a unique fragrance and depth to the tea, and these teas tend to age better over time.

Differences in Dry Leaves

So, what kind of differences will we see in the Rougui tea, grown in these different environments?

Here’s a little tip:

- If you find the dry leaves don’t have much aroma, try pre-warming the gaiwan with some hot water. After you warm the gaiwan, add the dry leaves, cover it, and shake it a bit.

- This will really bring out the aroma of the dry leaves. It’s a neat little trick that I think will make you appreciate the dry tea scent even more.

Observations on Dry Leaves

I started by inspecting the dry leaves and smelling the dry tea aroma.

- Wuyi Rougui (Zhoucha): This one has the lowest quality appearance. There are some tea stems, broken leaves, and the color is quite mixed—some are dark gray, others are brown.

- Wuyi Rougui (Banyan) and Wuyi Rougui (Zhengyan): The leaves are much more complete, and you can’t tell much difference just by looking. Both have some yellowish leaves, which suggests they were harvested when the leaves were less tender.

- Wuyi Rougui (Core Zhengyan): The leaves are noticeably smaller and tighter, which indicates they were picked from younger, tender leaves. The aroma is much more intense after shaking, with Core Zhengyan having the most pronounced dry tea fragrance, while Zhoucha is much weaker.

A fun fact: for twisted-leaf Oolong teas, if the leaves are tighter and thinner, that usually means they were picked younger. If the leaves are thicker, it typically means they were harvested from older leaves.

Brewing and Tasting

Now, onto the brewing and tasting. I brewed all of them using a white porcelain gaiwan, with 5g of tea and 100ml of water at 100°C. I steeped the first two for 10 seconds and the third for 15 seconds.

The differences between Zhengyan and Zhoucha were clear in the taste.

- The Zhengyan tea has a stronger, more pronounced mouthfeel with a noticeable aftertaste, especially along the sides and bottom of the tongue. The Zhoucha lacked that deep, lingering aftertaste and had a weaker fragrance.

I believe great Oolong should have no “wateriness”—you shouldn’t taste any watered-down flavors, and the roasted aroma should seamlessly blend with the oxidation levels. The tea should feel smooth and dense in the mouth, with a long-lasting aftertaste and fragrance. With bad Oolong, you’ll taste bitterness and too much smoke—likely because the oxidation or roasting wasn’t done well.

Some people say that Zhengyan tea feels so solid and full-bodied, almost like it has texture, and it’s true that the “rock taste” has a deep, lingering flavor that stays in the mouth. Unfortunately, I didn’t quite experience that today.

Maybe I need to compare it with some other teas grown in different places but made with the same techniques to really notice the difference. But honestly, the Wuyi Rock Tea craftsmanship is so top-notch, it’s hard to compare it to anything else.

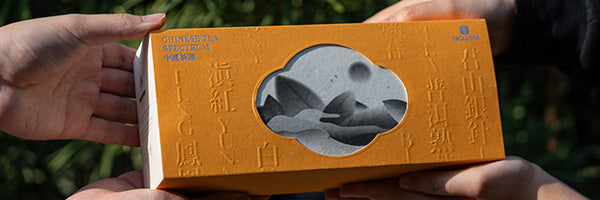

If you want to taste a collection of Wuyi Rougui Oolong Teas from different soil types, please take a look at our product. It includes Core Zhengyan Wuyi Tea (Core Zheng Yan), Wuyi Rou Gui (Zheng Yan), Wuyi Rou Gui (Ban yan Tea) and Wuyi Rou Gui (Zhou Cha)

Conclusion:

- Regional Characteristics: Wuyi Rock Tea is divided into distinct regions based on geography, soil type, and cultivation environment. Each region imparts unique qualities to the tea.

- Core Zhengyan: Produces the highest quality tea with a pronounced rock taste and lingering aftertaste.

- Banyan: Offers balanced flavors but less pronounced than Zhengyan.

- Zhoucha: Has a weaker fragrance and lacks a deep aftertaste compared to other regions.

- Processing Method: Charcoal roasting plays a vital role in enhancing the tea's depth and complexity, showcasing the craftsmanship and skill of traditional Wuyi Oolong techniques.

- Comparison Insights: The tasting highlighted significant differences in aroma, taste, and appearance among Zhengyan, Banyan, and Zhoucha teas, emphasizing the rich diversity within Wuyi Rock Tea.