Why is Chinese jasmine tea so richly fragrant and refreshing? Why do they say the aroma of top-grade jasmine tea isn’t added—it’s something that grows from deep within the leaf itself? And why can no other country’s floral tea compare?

Today, let’s uncover the secrets behind its magic through ancient Buddhist texts, modern scientific studies, and royal court archives.

A Sacred Flower in Buddhist Lore: A Sacred Beginning

1. Offerings in Buddhism

Jasmine (known in Sanskrit as Mallikā) has been regarded as a sacred flower since the early days of Buddhism. Ancient texts such as the Mahāprajñāpāramitopadeśa mention jasmine and Inula Flower as offerings to the Buddha due to their pure and intense fragrance. According to legend, the Shakyamuni once preached in a jasmine garden in Magadha, where the scent of the flowers became intertwined with the teachings of enlightenment. Since then, jasmine has been known as the "Fragrance of Enlightenment."

During the Western Han Dynasty, as Buddhism spread to China via the Silk Road, jasmine arrived in Fuzhou. At first, it wasn’t used for tea but served as a floral offering in Buddhist temples. Monks would place fresh flowers and tea leaves together before the Buddha, and accidentally discovered that tea could absorb the floral fragrance. This is the earliest prototype of Chinese jasmine tea.

2. Zen Tea: A Harmonious Tradition Backed by Science

In ancient Chinese poetry, jasmine was linked to purity and calm. But now, science backs it up:

- A 2022 study by Zhejiang University found that benzyl benzoate—a compound in jasmine tea—can enhance the activity of GABA receptors by 2.1 times, promoting relaxation. (Food Chemistry, Vol. 381)

- A 2021 study from Kyoto University showed jasmine aroma reduced anxiety levels by 18.7%, similar to the effects of 10 minutes of mindfulness meditation. (Journal of Ethnopharmacology)

This resonates with the Zen tea practices of Mount Emei, where monks have used jasmine-scented tea since the Ming Dynasty to “cleanse the mind and inspire meditation,” as recorded in the Eshan Gazetteer.

The Epic Evolution of Jasmine Tea Scenting

1. Southern Song Dynasty: Fragrance and Medicine from the Same Source (1131–1279)

The earliest known record of jasmine scenting in China appears in Zhao Xigu’s Diao Xie Lei Bian (c. 1240) from the Southern Song Dynasty. It states:

"Use three parts of half-bloomed jasmine flowers and one part of premium tea. For every jin (500g) of tea, mix in twelve liang (approximately 450g) of flowers. Layer them alternately in a sealed tin jar and keep it closed for five days."

Residue of jasmine compounds found inside a Southern Song tin tea jar unearthed in Fujian confirms that this technique was already well developed at the time. In fact, it closely resembles the jasmine scenting methods still used today.

Back then, jasmine tea was a niche beverage favored by scholars and literati for its health benefits. They referred to it as fragrant tea, believing it could "soothe the liver and ease depression"—an idea that resonated with both Buddhist offering rituals and the traditional Chinese medicine concept that fragrance and medicine share the same origin.

2. Ming and Qing Dynasties: Imperial Aesthetics (1368–1911)

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the craft of jasmine tea scenting became increasingly refined. In his 1886 work Records of Fujian’s Unique Products, Qing Dynasty author Guo Bocang wrote: “Jasmine must be picked at 3–5 a.m. with dew still on the petals, then gently dried on bamboo trays.”

Archived tea records from the Guangxu period show that jasmine tea offered to the imperial court—specifically the “Double-Scented Jasmine”—had to be hand-sorted by skilled female workers to ensure every flower remained intact.

According to Imperial Tribute Lists preserved in China’s First Historical Archives, the “Jasmine Sparrow Tongue” tea sent from Fujian in 1896 (the 22nd year of Guangxu's reign) was praised as having “a fresh and elegant aura, distinct from ordinary teas,” and became a seasonal favorite in the late Qing court.

It was during this time that traditional techniques such as layering jasmine flowers in bamboo trays and stirring the tea with bare feet were developed. Empress Dowager Cixi was especially fond of jasmine tea that had undergone two rounds of scenting—known as “shuang xun”—for its exceptionally vivid and lingering fragrance.

3. Modern Times (1949–Today): Scientific Precision

In the modern era, artisans refined the process further with techniques like “The flowers are only removed after seven rounds of scenting”, where each round uses fresh jasmine flowers, and the final infusion skips drying to preserve the natural vibrancy of the aroma.

Scientific analysis shows that repeated scenting breaks down tea proteins into more amino acids, resulting in a smoother texture and a subtle rock sugar sweetness.

Today, jasmine tea production is more precise than ever:

- Moisture in the tea base is kept between 4.5 - 5%;

- Re-firing temperatures are strictly controlled between 80 – 100°C;

- Scenting rooms follow specific humidity and temperature standards;

- Traditional manual flipping in bamboo trays is gradually being replaced by intelligent machines.

Yet, even with modern technology, true jasmine tea still relies on meticulous care for every flower and every leaf.

The Flavor Geography: Jasmine’s Genetic Lock at 26°N

Many people wonder—can other countries make jasmine tea as good as China’s?

The answer: It’s extremely difficult.

Exclusive jasmine variety: China’s single-petal jasmine has a delicate, crystal-clear fragrance that other regions can’t replicate.

Unique climate and soil: Especially in areas like the Min River Basin, conditions are ideal for cultivating both tea and jasmine.

Complex scenting process: A top-tier jasmine tea goes through 81 steps. It’s a slow, labor-intensive craft and can’t be rushed.

While countries like India and Vietnam also produce jasmine tea, they usually just mix flowers and tea or use artificial flavoring. The result is a flatter, more superficial taste that lacks the complexity and lasting charm of Chinese jasmine tea.

Japan also makes floral teas, but mostly by scenting green tea in a way that’s more about aroma layering than the deep tea-flower fusion found in China.

True Chinese jasmine tea is rich, layered, and soulful. It takes time, precision, and passion.

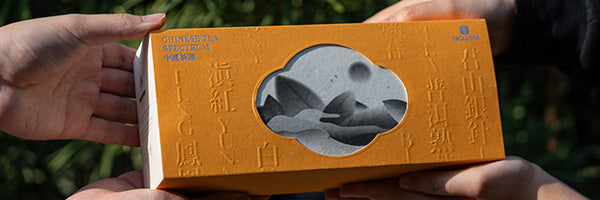

The number of scenting rounds is a key factor in determining the intensity of jasmine tea’s aroma. But does more scenting always mean a stronger fragrance and better taste? This product holds the answer. It features jasmine teas scented 3, 5, 7, and 9 times—crafted using traditional methods that showcase the uniquely Chinese art of floral infusion.

A Floral Renaissance in Modern Times

When people think of jasmine tea, they usually picture the classic version with green tea. But today, innovative artisans are reimagining scented teas with bold combinations and creative flair.

1. New Tea Bases

Traditionally, jasmine tea used green tea as its base. But now, we’re seeing a broader range of tea types being paired with flowers:

- Oolong + Flowers

High-aroma oolongs like Tie Guan Yin or Phoenix Dancong are paired with jasmine or gardenia to create “Jasmine Oolong,” offering deeper layers of fragrance.

- White Tea + Flowers

Delicate teas like Silver Needle or Shou Mei are scented with jasmine or honeysuckle. The result? A soft, sweet profile with floral complexity.

- Dark Tea + Flowers

Teas like Pu-erh or Liu Bao are paired with jasmine, rose, or chrysanthemum to create “Floral Dark Tea.” Thanks to dark tea’s strong absorption capacity, these teas lock in fragrance while offering health benefits.

2. New Flower Pairings

Besides having a richer variety of tea bases, the flower combinations are also becoming bolder and more interesting.

- Osmanthus + Black/Oolong Tea

Using traditional scenting methods, osmanthus pairs beautifully with black teas (like Lapsang Souchong) or oolongs (like Tie Guan Yin). The result: a rich and cozy “Autumn Osmanthus” flavor. Take a sip of “Osmanthus Red Tea” or “Osmanthus Oolong,” and you’ll taste rich, sweet aromas that are full of autumn vibes.

- Rose + Pu-erh/White Tea/Red Tea

Rose petals balance the earthy notes of Pu-erh, the sweetness of white tea or mellow taste of black tea, resulting in gentle yet complex teas like “Rose Pu-erh”, “Rose White Peony” or "Rose Black Tea".

- Chrysanthemum + Green/Dark Tea

Hangzhou white chrysanthemum combined with Longjing green tea or Anhua dark tea offers a refreshing brew perfect for summer detox and cooling.