Where did oolong tea originate, and what fascinating stories lie behind its history? Let’s dive into the past and present of oolong tea and explore how it became the beloved tea we enjoy today.

1. Where did Oolong tea origin?

When it comes to the origin of oolong tea, different people have different opinions. Some say it’s Wuyi Mountain, others say Anxi. We were curious too—so we dug into a lot of historical sources.

One of the most widely accepted views is that oolong tea originated in the Wuyi Mountain area of northern Fujian (Minbei), a region known as one of China’s oldest tea-producing areas. The main production areas for Minbei oolong tea are located within Nanping City, including Wuyi Mountain, Jianyang, and Jian'ou.

2. Why Did Oolong Tea Originate in the Wuyi Mountains of Northern Fujian?

Why is Wuyi Mountain of Minbei considered the birthplace of oolong tea? In ancient China, the Minbei region was known as Jianzhou, which roughly corresponds to today’s Nanping area. Tea produced there was called Jian Cha (建茶). Jian Cha became known during the Tang Dynasty. Over time—through the ups and downs of wars, government policies, and shifting markets—it gradually evolved into what we now know as Wuyi rock tea.

(1) Tang Dynasty — The Rise of Jian Tea

According to historical accounts, the earliest form of tea in northern Fujian was known as Yangao Cha (研膏茶), commonly referred to as “slice tea(Pian Cha)”. It’s said that during the Tang Dynasty (around 780–783 AD), a regional official named Chang Gun in Fujian created this tea by steaming tea leaves, grinding them into a paste, pressing them into cakes, and then baking them.

By the Yuanhe period of the Tang Dynasty (806–820 AD), this technique continued to evolve in the Wuyi Mountain area, giving rise to a new version called Lamian Cha (腊面茶). Around that time, a scholar named Sun Qiao wrote an essay titled Song Cha Yu jiao Xing Bu Shang Shu(送茶与焦刑部书), in which he personified the tea from Wuyi Mountain and called it “Wan Gan Hou” (晚甘侯). This is considered the earliest written record referring to Jian Cha.

(2) Song Dynasty — Beiyuan Tea Becomes Imperial Tribute Tea

By the time of the Northern Song Dynasty(960-1127 AD), Jian Cha had entered its golden age. Represented by the Beiyuan tribute tea, Jian Cha became an offering to the imperial court, with the finest quality coming from the Wuyi Mountain region. In the royal tea gardens of Beiyuan, steamed green tea leaves were pressed into cakes using ornate molds featuring dragon and phoenix designs. These were called Dragon-Phoenix Tribute Cakes (Longfeng Tuan Cha) and were beloved by the royal family and admired by scholars and poets alike.

Within just a century of its rise, the variety of Jian Cha expanded dramatically—from a dozen types to more than forty or fifty. Both the craftsmanship and the quality of tea from this region far surpassed other tea-producing areas of the time. This remarkable progress laid a solid foundation for the later development of oolong tea.

(3) Yuan Dynasty—Wuyi Tea Becomes the New Imperial Tribute

During the Yuan Dynasty (around 1302 AD), the imperial court established a “Royal Tea Garden(Yu Cha Yuan,御茶园)” in Wuyi Mountain to better supervise the production of tribute teas. Under government oversight, both the quality and craftsmanship of Wuyi tea continued to improve. Over time, Wuyi tea gradually replaced Beiyuan tea as the most representative form of Jian Cha. The most famous tea from Wuyi during this period was Shi Ru Cha (石乳茶), a type of steamed green tea.

An interesting tradition still exists today called “Han Shan Ji Cha(喊山祭茶).” It stems from this period when officials would lead workers in a ritual on the awakening of Insects, shouting “Tea is sprouting! Tea is sprouting!” as a way to pray for a good harvest.

(4) Ming Dynasty — The Stage Was Set for the Birth of Oolong Tea

Because the production of steamed tea cakes was so labor-intensive and costly, Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang of the Ming Dynasty issued a decree in 1391 to “abolish dragon cakes and switch to loose-leaf tea.” The processing of Wuyi tea was gradually simplified, evolving from steamed green tea cakes to sun-dried and steamed loose-leaf tea, and later, by the late Ming dynasty, to pan-fired green tea.

As this transition unfolded, the Royal Tea Garden was gradually abandoned. Tea cultivation also shifted to the Three Pits and Two Gullies(三坑两涧)—the very heart of modern Wuyi rock tea production.

(5)Qing Dynasty — Oolong Tea Processing Gradually Matures

In the early Qing Dynasty(1650-1653 AD), Yin Yingyin, the magistrate of Chong'an County (present-day Wuyishan City), invited monks from Huangshan in Anhui to produce Songluo tea—a type of pan-fired green tea. According to Min Xiao Ji, a local record written by Zhou Liang-gong, this tea would turn reddish or even purplish after being stored for several months.

Tea experts like Yao Mingyue, along with experienced local farmers, have offered an inference: since tea trees in Wuyi Mountain grow scattered across various peaks, tea pickers had to travel from mountain to mountain. During this process, the freshly picked leaves would get jostled and rubbed together in the baskets. On top of that, transport took quite a while, and the leaves had often lost some moisture, softened, and developed red edges. Teas made from these semi-oxidized leaves still had excellent aroma and flavor—but would continue to darken over time, turning red or purple naturally.

Observing this change, the monks began experimenting and refining the process. Over time, their adjustments led to the development of the zuoqing (做青) stage in tea-making—and with it, the birth of oolong tea.

Over time, the oolong tea-making process continued to evolve. During the reign of Emperor Kangxi in the Qing Dynasty(1708-1720 AD), a tea text by Wang Fuli called Cha Shuo (茶说) documented key steps such as sun-withering, yaoqing, fixation, and roasting. These techniques are remarkably similar to those still used in crafting Wuyi rock tea today, suggesting that by that point, the oolong processing method had already matured. With this, Wuyi Mountain came to be recognized as the birthplace of oolong tea.

From there, the craftsmanship of Wuyi rock tea gradually spread from the Wuyi Mountain area to places like Jian'ou, Anxi, Guangdong, and Taiwan—eventually giving rise to the four major oolong-producing regions we know today: Northern Fujian, Southern Fujian, Guangdong, and Taiwan.

3. Our product recommendations

(1)If you want to taste the flavors of Northern Fujian oolong tea, you're welcome to purchase our Minbei Oolong Tea Set.

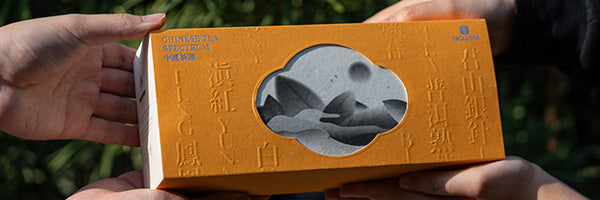

Northern Fujian Oolong Collection--6 representative flavors 100g

(2) If you’d like to taste some of the most famous oolong teas from China’s four major producing regions, we’ve put together a carefully selected sampler for you. It includes ten different oolongs—such as Da Hong Pao oolong tea, Wuyi Rock Tea, Mi Lan Xiang, Oriental Beauty tea, Tie Guan Yin, Jasmine Oolong Tea, and more—so you can enjoy ten distinct flavors in one set.