Exploring Oolong Tea Regions

The Untold Stories of Guangdong Oolong Tea

How did Guangdong Oolong tea grow from just two humble tea cultivars into one of the regions with the richest variety of aromas and tea tree varieties? This blog will tell you the story.

What Is Guangdong Oolong Tea? A Beginner's Guide with 6 Must-Try Teas

When people think of Chinese oolong tea, places like Wuyi or Anxi might come to mind first. But there's another region quietly making waves: Guangdong. Tucked away in southern China, Guangdong has crafted a bold, floral-forward oolong tea that feels unlike anything else.

Not Just Tie Guan Yin: Discovering the Full Range of Minnan Oolong Teas

Chinese oolong tea is mainly produced in four regions: Southern Fujian (Minnan), Northern Fujian (Minbei), Guangdong, and Taiwan. Today, we want to focus on Minnan oolong.

The main production areas for Minnan oolong tea are around Quanzhou (Anxi and Yongchun), Zhangzhou (Hua’an and Pinghe), and Longyan’s Zhangping area.

1. How Minnan Oolong Varieties Evolved

Back in the Kangxi period of the Qing Dynasty (1600s), a monk in Yongchun grafted local citron trees with tea plants from Anxi. That gave rise to Yongchun Fo Shou, known for its unique fruity fragrance and mineral-rich taste.

In the 18th century, Minnan oolong entered its golden age. During the Qianlong reign, a man named Wang Shirang from Anxi discovered a strange tea tree and processed its leaves into something so unique that he offered it to the emperor. Because the tea was "as heavy as iron and shaped like the Goddess of Mercy (Guanyin)," it got the name Tie Guan Yin. With its distinct rocky flavor and growing export demand in Southeast Asia, it quickly became a major export tea.

At that time, Minnan oolong was mainly made in the traditional rich-aroma style—meaning it had a higher oxidation level than most modern versions. The roasting process followed the rule of "light roast for high-quality leaves, heavier roast for lower-grade ones."

During the Xianfeng period, tea farmers in Anxi developed Huang Jin Gui (Golden Osmanthus), famous for its strong osmanthus-like fragrance. It became one of the iconic high-aroma oolongs from the region.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, Minnan tea producers started developing new cultivars for overseas markets. Two important ones were Mei Zhan, which has strong fruity notes and great durability across multiple infusions, and Da Ye Oolong (Big Leaf Oolong), known for its rich, smooth taste and sweet caramel-like aroma. These were often used in blends.

In the late 20th century, technology gave Minnan oolong another boost. In the 1980s, Bai Ya Qi Lan, a new variety with a refreshing orchid fragrance, was discovered in Pinghe County. Then in the 1990s, the Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences developed new cultivars like Jin Guan Yin and Huang Guan Yin by crossing Tie Guan Yin with Huang Dan, adding new layers of aroma to Minnan oolongs to meet changing market preferences.

Also in the 1990s, Taiwanese tea companies introduced lighter oxidation (15–25%) and low-temperature roasting techniques to Minnan. This gave rise to the light-aroma Tie Guan Yin, a fresher, more delicate style that quickly became mainstream—especially among younger tea drinkers who preferred a cleaner, crisper taste.

2. Crafting Style of Minnan Oolong

When it comes to processing, Minnan oolong actually started by borrowing techniques from Minbei's Wuyi rock tea (Yancha)—especially the charcoal roasting style. Over time, it developed its own signature methods. Later on, with the influence of Taiwanese lightly oxidized oolongs, Minnan producers began crafting what’s now known as the light-aroma style.

One signature step in Minnan oolong processing is ball-rolling (called baorou in Chinese), which gives the leaves their signature tightly curled, semi-ball shape. So it’s not just Tie Guan Yin that looks like that—many Taiwanese and Minnan oolongs share this shape.

Nowadays, the same tea cultivar is often made in two different styles:

● Nongxiang (rich aroma) — more roasted and oxidized

● Qingxiang (light aroma) — greener, lighter, and fresher

Since much of Minnan oolong is exported, this split is pretty visible on the international market. For example, if you’ve seen “green oolong” on Amazon, that’s usually light-aroma Tie Guan Yin. “Black oolong,” on the other hand, refers to the heavily roasted, darker style, often made specifically for export.

Ironically, this "black Tie Guan Yin" style is rarely consumed in China—most local tea drinkers don’t go for oolongs that are super heavily roasted.

(1) Light Aroma Tie Guan Yin

This style is lightly oxidized (about 15–25%), gently withered in the sun, and roasted at low temperatures. It’s known for its “three greens”: green dry leaves, greenish tea liquor, and green leaf bottoms. The aroma is clean and floral, often compared to orchids.

If you’re new to oolong or coming from green tea, we’d recommend this style—Qingxiang Tie Guan Yin feels very fresh, smooth, and accessible.

Now, even within the light-aroma category, there are different sub-styles in China:

● Traditional Zhengwei (classic flavor) Tie Guan Yin

Medium oxidation

Leaves are fixed (sha qing) before 10 am the next day

Color is dark green or almost black-green

The flavor is round and balanced

Many Anxi locals prefer this style—some say it's easier on the body from a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) perspective.

● Xiaoqing (fresh-green style)

Light oxidation

Sha qing happens later (between noon and 6 pm)

Leaves are a brighter, sandy-green color

Aroma is fresher, lighter, with more green notes

Interestingly, the lightest-oxidized Tie Guan Yin can start to resemble Taiwanese oolongs in both taste and appearance.

(2) Rich Aroma (Nongxiang) Style Tie Guan Yin

This style usually goes through medium oxidation (around 40%), and is traditionally charcoal roasted, giving it that deep, toasty flavor. One signature feature is the "red-edged green leaves" (these are called hongbian in Chinese)—you can see the leaf edges turn reddish after brewing.

The aroma tends to be richer, with notes of ripe fruit and a noticeable roast.

This heavy roast was originally done for export reasons, to help stabilize the tea for shipping.

These days, you’ll also see some “modern” rich-aroma Tie Guan Yin in China. Basically, it’s light-aroma TGY that’s been lightly re-roasted to deepen the flavor. This style only uses low-temperature, slow roasting (what we call wenhuo)—not the intense fire used in traditional roasting. The result is actually kind of cool—it keeps the floral and fruity notes, but adds a gentle layer of roast.

You can actually tell the difference by looking at the brewed leaves:

● Traditional roasted Tie Guan Yin: the “red edges” are very obvious

● Modern style: leaf edges stay mostly green

Unfortunately, traditional charcoal roasting in Minnan almost disappeared for a while. The craft became marginalized, many old tea masters retired, and the technique almost died out. Meanwhile, in Minbei (northern Fujian), the Wuyi Yancha community stuck with their traditional charcoal roasting, building a loyal following and keeping the craft alive. That’s why Wuyi rock teas still hold a strong position in the high-end tea market.

So, yeah—light-aroma Tie Guan Yin kind of "won" in the market, especially among younger drinkers and for export. But at what cost?

Are we trading “depth and uniqueness” for “speed and simplicity”?

Are we slowly forgetting the craft and the deeper flavors that used to define these teas?

Some producers in Minnan are starting to reintroduce traditional charcoal roasting to appeal to more serious tea drinkers and the high-end market. But to be honest, it’s still a tough sell domestically—many seasoned tea drinkers in China are skeptical about the newer versions of this revival.

3. Minnan Oolong Recommendations – There's More Than Just Tie Guan Yin

When people think of Minnan (Southern Fujian) oolong tea, Tie Guan Yin is usually the first thing that comes to mind—but there's a lot more to explore.

Minnan oolong doesn’t need to chase complexity for the sake of it. Take just light-aroma Tie Guan Yin, for example—there are already 4 different processing styles floating around. We think instead of going wide with too many variations, Minnan oolong should double down on what makes it unique and easy to remember for tea lovers. In our opinion, that core identity lies in its traditional craftsmanship.

Some general traits of Minnan oolong compared to other regions:

● Lower oxidation overall (lighter than Guangdong oolongs)

● Light-aroma styles are usually not roasted, or only very lightly roasted

● Rich-aroma styles still have less oxidation and lighter roasting than Wuyi rock teas, so the liquor feels smoother and lighter

● This also means the character of each tea cultivar stands out more clearly in the cup

A few examples:

● Meizhan (梅占) – has this lovely plum fruit aroma

● Daye Oolong (大叶乌龙) – gives off a more earthy, old-tree flavor

● Zhangping Shui Xian (漳平水仙) – super balanced and smooth

● Tie Guan Yin (铁观音) – of course, known for its fresh, rich aroma and creamy texture

● Traditional-style Huangjin Gui (黄金桂) – with its osmanthus-like fragrance

● Baiya Qilan (白芽奇兰) – super clean orchid note

● Yongchun Fo Shou (永春佛手) – bold and citrusy, with a unique character

So yeah, while Tie Guan Yin is the superstar, there’s a whole lineup of Minnan oolongs worth discovering—each with its own vibe, and rooted in a lighter, more delicate style that really highlights the character of the leaf.

(1) Tie Guan Yin (Light-Aroma & Rich-Aroma)

Tie Guan Yin is often called the “King of Minnan Oolong”—and for good reason. It's still the gold standard when it comes to Southern Fujian oolong craftsmanship. The tea is made from a unique cultivar known as “Red Heart, Twisted Tail Peach”, and its signature “Guanyin Yun” (a lingering orchid-like aftertaste) sets it apart from other oolongs.

Traditionally, there are two main styles:

● Light-Aroma Tie Guan Yin – known for its crisp orchid fragrance and sweet, refreshing taste.

● Rich-Aroma Tie Guan Yin – made using traditional charcoal roasting, with baked fruit notes, roasted sweetness, and sometimes a warm, toasty sweet potato aroma when hot.

In recent years, a third style has emerged: Aged Tie Guan Yin (陈香型), which undergoes deep roasting and aging over time. This combines Minnan's light oxidation style with Wuyi-style deep roasting, offering an even more layered experience.

If you're into floral, sweet teas with a light body, Light-Aroma Tie Guan Yin is a great place to start. If you're looking for something more warming and full-bodied, go for Rich-Aroma Tie Guan Yin—but expect it to be lighter than Wuyi rock teas, with more fruit and less heavy charcoal intensity.

Click the link to learn more about light-aroma Tieguanyin and strong-aroma Tieguanyin.

(2) Huangjin Gui (a.k.a. Huang Dan)

Huangjin Gui, or "Golden Osmanthus," was first cultivated in the mid-1800s in Anxi County, Fujian. It's one of the earliest-sprouting high-aroma cultivars in Minnan, famous for its intense floral scent, said to resemble osmanthus, gardenia, or Asian pear—earning it the nickname “Fragrance That Pierces the Sky” (透天香).

This tea is lightly oxidized and extremely fragrant, perfect for fans of teas that feel almost like green tea, but with a unique floral twist.

One tip: Stick to the traditional processing methods when trying Huangjin Gui. Some modern versions use very light oxidation and end up tasting too similar to light Tie Guan Yin—losing their unique charm.

Today, about 15% of Anxi's tea fields grow Huangjin Gui, with around 60% of it exported, mainly to Southeast Asian markets.

If you're interested in Huang Jin Gui, feel free to click the link to learn more.

(3) Zhangping Shui Xian (漳平水仙)

Zhangping Shui Xian is a compressed oolong tea from Zhangping, Fujian—the only oolong that’s traditionally pressed into cakes. It was created in 1914 by a tea master named Deng Guanjin, who combined techniques from both Northern and Southern Fujian. The tea uses the Shui Xian cultivar, named after its natural narcissus-like fragrance.

Zhangping Shui Xian is a UNESCO-recognized Intangible Cultural Heritage (since 2022), and its traditional production involves slow charcoal roasting over 2–3 days. While some modern producers use electric roasting, true traditional versions stick with charcoal, which gives the tea a soft smokiness and rounded sweetness.

Flavor-wise, it has a lovely combo of orchid and osmanthus floral notes, slightly sweeter and smoother than light Tie Guan Yin. There's no grassy note at all, and the liquor has a nice silky texture.

That said, if you compare it directly with Tie Guan Yin, you might find the aroma less sharp or showy, but if you enjoy balanced, sweet, floral oolongs with a gentle personality, this one is well worth trying.

If you're interested in Zhangping Shui Xian, feel free to click the link to learn more.

(4) Yongchun Fo Shou (永春佛手)

Yongchun Fo Shou is a rare citrus-fragrant oolong from Yongchun County, Fujian. Grown at elevations of 600–900 meters, this tea has a fascinating origin: monks in the late 1600s are said to have grafted tea plants onto a Buddha’s Hand citron tree, creating a cultivar with leaves shaped like a Buddha’s hand and a distinct citrus aroma.

Fo Shou tea is unique among Minnan oolongs—it’s the only one named after a fruit, and it offers a mix of:

● Asian pear

● Citrus peel

● Creamy, milky notes

It’s especially interesting to drink once it cools down—you’ll notice an evolving aroma that feels crisp, complex, and almost meditative. No wonder Master Hongyi once wrote a poetic line for it: “Yongchun Fo Shou – A Tea Meant for Kindred Spirits.”

If you're hunting for fruit-forward oolong with personality, this one delivers something you won’t find anywhere else.

If you're interested in Yongchun Fo Shou, feel free to click the link to learn more.

(5) Mei Zhan (梅占)

Mei Zhan originated in the early 19th century during the Jiaqing to Daoguang era of the Qing Dynasty, first discovered in Lutian Town, Anxi. It’s suitable for both oolong and black tea and is prized for its distinctive plum blossom aroma. The leaves are thick and crisp but lose tenderness quickly, so they must be picked young and gently shaken to release their signature orchid-like fragrance. After oxidation, Mei Zhan often develops floral notes reminiscent of plum blossoms or a subtle stone-fruit sweetness, making it a rare cultivar that combines both floral and fruity characteristics.

There are both light and traditional roasted styles of Mei Zhan, but the classic heavy-roast version is more common. This style is lightly to moderately oxidized and roasted at medium heat (80–100°C), producing a rich, layered liquor with a signature “red edges on green leaves” appearance in the brewed leaves and enhanced steeping endurance. Influenced by Taiwanese tea processing, some producers have developed a lightly oxidized (15–25%), low-temperature roasted version, retaining freshness and a delicate orchid aroma.

If you're interested in Mei Zhan, feel free to click the link to learn more.

(6) Da Ye Oolong (大叶乌龙)

Da Ye Oolong, or “Large-leaf Oolong,” is a traditional Minnan cultivar that originated from Tongfa Mountain in Shanping, Changkeng, Anxi. It has been documented since the Qing Dynasty. Though much of it was replaced by Tie Guan Yin during the tea boom of the 1990s, some old-growth trees were preserved thanks to their unique flavor and excellent re-steeping qualities.

Tea made from wild-grown or older trees offers a deep, full-bodied mouthfeel and lingering aftertaste, while bushes from pruned or younger plantations tend to produce a lighter-bodied tea with a higher aroma but less complexity. Characteristic notes include caramel, wood, and in older trees, a distinct "cong wei" (roasted forest aroma).

If you're interested in Da Ye Oolong, feel free to click the link to learn more.

(7) Bai Ya Qi Lan (白芽奇兰)

Bai Ya Qi Lan is a rare oolong cultivar unique to Pinghe County in Fujian and is one of the five most renowned oolongs from the province. It’s known for its enchanting orchid fragrance and honey-like sweetness. The name translates to “White Bud Strange Orchid,” referencing both the pale green color of the tea buds and their distinctive floral aroma.

Legend has it that during the Qianlong era of the Qing Dynasty (1735–1795), a tea tree with pale buds and a strong orchid scent was discovered in Pengxi Village, Qiling Township. When processed into tea, the aroma was so unusual that the variety was named “Qi Lan” (strange orchid).

Today, Bai Ya Qi Lan is primarily cultivated in Qiling Township and the surrounding regions, including Daqin Mountain—Fujian’s tallest peak at 1,544.8 meters. The dry leaves carry a soft orchid scent, and once brewed, the aroma becomes more pronounced, layered with notes of honey and citrusy fruit (such as pomelo).

If you're interested in Bai Ya Qi Lan, feel free to click the link to learn more.

How to Brew Rolled (Ball-Shaped) Oolong Tea

Teaware:

For light and floral oolongs (usually lightly oxidized and lightly roasted), a white porcelain gaiwan works best—it brings out the clean aroma without interfering with the taste.

For richer, roasted, or charcoal-baked oolongs, a Yixing clay teapot can enhance the depth of flavor. But keep in mind: with clay pots, it’s “one tea, one pot”—otherwise, the flavors can mix. If you don’t have a dedicated Yixing pot, a porcelain gaiwan is always a safe and versatile choice.

Water Temperature:

Use fully boiling water—100°C (212°F). If the temperature drops below 90°C (194°F), the aroma won’t come through properly, and the tea will taste thin.

Tea-to-Water Ratio:

If you’re using a 100ml gaiwan, add about 5 grams of tea. That’s roughly a 1:20 tea-to-water ratio. You can tweak the amount slightly based on how strong you like it.

Water Quality:

Use weakly alkaline spring water or purified water if possible. Avoid tap water that has a lot of minerals or a weird taste. If tap water is your only option, boil it for 3–5 minutes to help remove some impurities. You can also let it sit uncovered in a glass or ceramic container for 12–24 hours to air out. Using an iron kettle can also help improve the water’s taste.

Warm Your Teaware:

Rinse your gaiwan and cups with boiling water before brewing. This helps bring everything to temperature so the tea can release its full aroma.

Rinse the Tea (Wake-up Rinse):

Pour boiling water over the dry leaves and quickly discard the rinse after about 8–10 seconds. This helps remove any dust and wakes the tea up.

Pouring Technique:

Pour the water in a circular motion along the inner wall of the gaiwan. This helps the leaves unfurl evenly and enhances the release of aroma.

First Brews:

For the first few brews (especially the first 1–3), keep the steep time short—about 10 seconds.

Later Brews:

Gradually increase the steeping time by 5–10 seconds with each infusion. High-quality oolongs can easily go 7–10 infusions or more. The better the tea, the more steeps you'll get.

Drain Completely:

After each brew, make sure to pour out all the tea. Leaving any liquid behind can oversteep the leaves and make the next cup taste bitter.

Our Products:

1. Our Minnan Oolong Collection features a curated selection of classic varieties, including Light Aroma Tie Guan Yin, Rich Aroma Tie Guan Yin, Bai Ya Qi Lan, Yongchun Fo Shou, Huang Jin Gui, and more. Each tea offers its unique flavor profile, carefully chosen to take you on a journey through the authentic taste of Minnan Oolong tea!

Southern Fujian Oolong Collection--8 unique historical flavors 100g

2. This collection features Minnan Shui Xian Oolong teas from five different years: 1994, 2004, 2014, 2020, and 2024. As the tea ages, its flavor transforms in fascinating ways—evolving from the bold aroma of charcoal roasting to gentle woody notes, and eventually into the deep, mellow fragrance of aged tea. It’s this remarkable journey of flavor that has earned aged Oolong its devoted following.

Aged Oolong Tea Comparison Set—1994 to 2024 100g

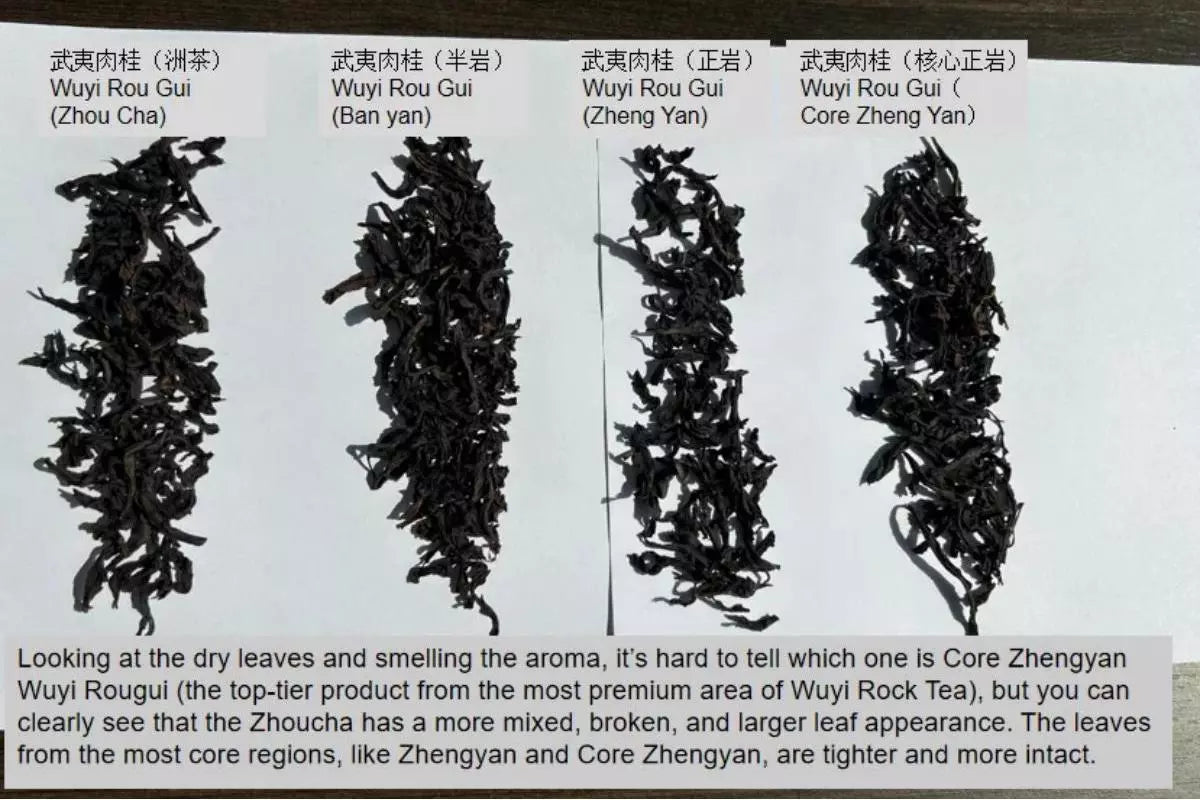

Today, I did a tasting comparison of four Wuyi Rougui teas. They were all made by the same master, using the same process, but each comes from a different part of Wuyi Mountain.

One is from the core Wuyi Rock Tea region (the Three Pits and Two Streams area), one is from the Zhengyan area, one is from the Banyan area, and the last one is from the Zhoucha area.

What is Wuyi Rock Tea?

You might be wondering: if they’re all Wuyi Rock Teas, what’s the difference between these regions? Well, before diving into that, let me give you a quick intro to what Wuyi Rock Tea is and how it’s categorized.

According to the national standards for Wuyi Rock Tea, it’s defined as tea made from specific tea tree varieties, grown within Wuyi Mountain’s unique natural ecosystem, and processed using traditional techniques. This tea has a distinctive “Yan Yun” (rock aroma and floral fragrance) quality.

For tea to be considered Wuyi Rock Tea, it must meet these criteria:

Grown in Wuyi Mountain’s 2798-square-kilometer area.

Made using the traditional processing method (shaped into twisted leaves).

Has the characteristic Yan Yun quality.

It is a protected geographical indication product in China.

Differences Between Tea Areas

Now, how are these different Wuyi tea areas (core Zhengyan, Zhengyan, Banyan, and Zhoucha) distinguished?

Core Zhengyan: Tea grown in the Three Pits and Two Streams region (including Huiyuan Pit, Niulankeng, Daoshui Pit, Liuxiangjian, and Wuyuanjian).

Zhengyan: Tea grown within the scenic area of Wuyi Mountain.

Banyan: Tea grown in the surrounding hills and semi-hilly areas.

Zhoucha: Tea grown on the plains and mountainous areas near the two rivers of Wuyi Mountain.

The main difference between these areas, aside from their geographical range, is the soil type.

The Zhengyan region has volcanic rock, red sandstone, and shale, while the Banyan region’s soil contains a mix of half-weathered rock and gravel. Zhoucha has alluvial soil from the three streams (Chongyang, Huangbai, and Jiuqu) near the Wuyi Mountain.

Charcoal Roasting vs. Electric Roasting

All of these teas have been traditionally charcoal roasted, not modern high-temperature baked. So how can we tell if it’s charcoal roasting or electric roasting?

Dry leaf color: If the dry tea leaves have a slightly grayish or whitish look, that’s usually a sign of charcoal roasting. Electric roasting, on the other hand, tends to preserve a greener color, without the noticeable white coating.

Taste: Charcoal roasted teas often have a smoky, fire-like taste.

Why does it matter whether it’s charcoal roasted or electric roasted? Traditional Wuyi Oolongs are charcoal roasted, which requires more skill and experience.

Electric roasting is quicker but doesn’t infuse the same depth of flavor. Charcoal roasting imparts a unique fragrance and depth to the tea, and these teas tend to age better over time.

Differences in Dry Leaves

So, what kind of differences will we see in the Rougui tea, grown in these different environments?

Here’s a little tip:

If you find the dry leaves don’t have much aroma, try pre-warming the gaiwan with some hot water. After you warm the gaiwan, add the dry leaves, cover it, and shake it a bit.

This will really bring out the aroma of the dry leaves. It’s a neat little trick that I think will make you appreciate the dry tea scent even more.

Observations on Dry Leaves

I started by inspecting the dry leaves and smelling the dry tea aroma.

Wuyi Rougui (Zhoucha): This one has the lowest quality appearance. There are some tea stems, broken leaves, and the color is quite mixed—some are dark gray, others are brown.

Wuyi Rougui (Banyan) and Wuyi Rougui (Zhengyan): The leaves are much more complete, and you can’t tell much difference just by looking. Both have some yellowish leaves, which suggests they were harvested when the leaves were less tender.

Wuyi Rougui (Core Zhengyan): The leaves are noticeably smaller and tighter, which indicates they were picked from younger, tender leaves. The aroma is much more intense after shaking, with Core Zhengyan having the most pronounced dry tea fragrance, while Zhoucha is much weaker.

A fun fact: for twisted-leaf Oolong teas, if the leaves are tighter and thinner, that usually means they were picked younger. If the leaves are thicker, it typically means they were harvested from older leaves.

Brewing and Tasting

Now, onto the brewing and tasting. I brewed all of them using a white porcelain gaiwan, with 5g of tea and 100ml of water at 100°C. I steeped the first two for 10 seconds and the third for 15 seconds.

The differences between Zhengyan and Zhoucha were clear in the taste.

The Zhengyan tea has a stronger, more pronounced mouthfeel with a noticeable aftertaste, especially along the sides and bottom of the tongue. The Zhoucha lacked that deep, lingering aftertaste and had a weaker fragrance.

I believe great Oolong should have no “wateriness”—you shouldn’t taste any watered-down flavors, and the roasted aroma should seamlessly blend with the oxidation levels. The tea should feel smooth and dense in the mouth, with a long-lasting aftertaste and fragrance. With bad Oolong, you’ll taste bitterness and too much smoke—likely because the oxidation or roasting wasn’t done well.

Some people say that Zhengyan tea feels so solid and full-bodied, almost like it has texture, and it’s true that the “rock taste” has a deep, lingering flavor that stays in the mouth. Unfortunately, I didn’t quite experience that today.

Maybe I need to compare it with some other teas grown in different places but made with the same techniques to really notice the difference. But honestly, the Wuyi Rock Tea craftsmanship is so top-notch, it’s hard to compare it to anything else.

If you want to taste a collection of Wuyi Rougui Oolong Teas from different soil types, please take a look at our product. It includes Core Zhengyan Wuyi Tea (Core Zheng Yan), Wuyi Rou Gui (Zheng Yan), Wuyi Rou Gui (Ban yan Tea) and Wuyi Rou Gui (Zhou Cha)

Conclusion:

Regional Characteristics: Wuyi Rock Tea is divided into distinct regions based on geography, soil type, and cultivation environment. Each region imparts unique qualities to the tea.

Core Zhengyan: Produces the highest quality tea with a pronounced rock taste and lingering aftertaste.

Banyan: Offers balanced flavors but less pronounced than Zhengyan.

Zhoucha: Has a weaker fragrance and lacks a deep aftertaste compared to other regions.

Processing Method: Charcoal roasting plays a vital role in enhancing the tea's depth and complexity, showcasing the craftsmanship and skill of traditional Wuyi Oolong techniques.

Comparison Insights: The tasting highlighted significant differences in aroma, taste, and appearance among Zhengyan, Banyan, and Zhoucha teas, emphasizing the rich diversity within Wuyi Rock Tea.

Four Types of Oolong Tea in China

Oolong tea, one of the six major categories of tea, is a partially fermented tea that combines the delicate aroma of green tea with the richness of black tea. Oolong tea originated in Fujian, China, and is crafted through processes such as withering, oxidation, fixation, rolling, and roasting after the plucking of new tea leaves. Today, there are many varieties of oolong tea, which can be roughly categorized based on their production regions into Minbei Oolong, Southern Fujian Oolong, Guangdong Oolong, and Taiwan Oolong. What are the distinctive characteristics of oolong teas from these four regions? Let's explore them together.

Minbei Oolong

"Fujian" refers to Fujian Province in China. Northern Fujian encompasses the northern region of the province, which includes famous tea-producing areas like Wuyishan, Zhenghe, Shaowu, Jian'ou, and Jianyang.

Minbei Oolong boasts a wide variety, with no fewer than a few hundred types. Its most notable features are the emphasis on tea varieties and roasting. Minbei Oolong teas undergo a heavier oxidation during the rolling process, without the kneading step. The dry tea leaves have a lustrous color, and they possess a ripe aroma. The tea liquor is bright orange-yellow, and the leaves exhibit a distinct combination of three red edges and seven green centers.

Representative oolong teas from Northern Fujian include Da Hong Pao, Tie Luo Han, Bai Ji Guan, Shui Jin Gui, Ban Tian Yao, Bu Zhi Chun, Wu Yi Shui Xian, Rou Gui, Jianyang Shui Xian, and Lao Jun Mei, among others.

Among these, Wuyi Rock Tea stands out as a well-known category of Minbei Oolong, characterized by its "rocky rhyme" (a unique mineral and floral fragrance). Wuyi Rock Tea is mainly produced in the Wuyi Mountain area, where tea bushes grow within rocky crevices. Varieties like Da Hong Pao, Tie Luo Han, Bai Ji Guan, and Shui Jin Gui belong to this category.

Minnan Oolong

Minnan Oolong, as the name suggests, refers to tea produced in the northern regions of Fujian Province, China. This area includes well-known tea-producing regions like Anxi, Yongchun, Hua'an, and Zhangping.

Minnan Oolong is renowned for its intricate craftsmanship, often described as "meticulous work yields fine results." It not only pursues a tight and well-rolled appearance but also offers a diverse range of styles. The appearance of Minnan Oolong teas is characterized by a curled semi-spherical or balled shape, which is tightly compact and robust.

The color typically ranges from sandy green to dark brown, with some teas displaying a reddish hue.

The aroma, mainly featuring the fragrance of orchids, is naturally rich and long-lasting. The flavor is mellow and returns with a sweet aftertaste.

Representative oolong teas from Minnan Oolong include Anxi TieGuanyin, Huangjin Gui, Yongchun Fo Shou, Minnan Shuixian, Zhangping Shuixian, and Bai Ya Qi Lan.

Among these, TieGuanyin and Huangjin Gui are the most famous and highly regarded. These two oolong teas are known for their unique appearance resembling the head of a dragonfly, their golden-hued liquor, the delicate and lingering aroma of orchids, and their ability to withstand multiple infusions while retaining their distinctive fragrance.

If you’re into Minnan oolongs, check out our Minnan Oolong Collection and enjoy eight teas in one go>>

Guangdong Oolong

Guangdong Oolong refers to teas produced in the eastern regions of Guangdong Province, including areas such as Chao'an, Raoping, Shantou, Jiedong, and Puning.

In terms of craftsmanship, Guangdong Oolong mainly draws on the strengths of Minbei Oolong while developing its own distinct character. Guangdong Oolong places a strong emphasis on post-fermentation and rolling, with its most notable feature being the pursuit of "mountain charm," particularly in its aroma. The appearance of Guangdong Oolong teas primarily consists of strip-shaped leaves, tightly rolled, robust, slightly twisted, and somewhat slender.

The color tends to be a lustrous greenish-brown or dark brown, often with small white spots resembling frog skin. In terms of aroma, Guangdong Oolong exhibits a variety of natural floral and fruity fragrances, with a strong and intense aroma. The flavor is rich, with a pronounced sweetness and significant aftertaste, making it suitable for multiple infusions.

Representative oolong teas from Guangdong Oolong include Fenghuang Dancong, Lingtou Danshu, Fenghuang Shuixian, Shiguping Wulong, and Raoping Sezhong, among others.

Among these, Fenghuang Dancong is a treasure, and it involves the cultivation of outstanding individual plants selected and propagated from the Fenghuang Shuixian tea tree population, with more than 80 different varieties.

Taiwan Oolong

Leveraging its unique ecological, climatic, and environmental conditions, various regions in Taiwan cultivate tea. The total area devoted to tea cultivation in Taiwan is approximately 23,000 hectares, with the primary focus on oolong tea.

Taiwan Oolong has its roots in Fujian but has undergone some modifications in its processing. A distinctive feature of Taiwan Oolong is the presence of stems within the tea leaves, but these stems tend to be relatively soft and contain more juice. Taiwan's unique kneading technique enhances the high-mountain tea's character, making Taiwan Oolong particularly renowned for its high-mountain charm. The appearance of Taiwan Oolong teas is primarily characterized by strip-shaped or semi-spherical leaves, tightly rolled and robust.

Taiwan Oolong comes in a wide variety of types, and the color varies depending on the specific variety. It is known for its diverse natural floral and fruity fragrances, as well as hints of creamy notes. The aroma is high, clear, and elegant, while the flavor is sweet, clean, and mellow.

Representative oolong teas from Taiwan include Dong Ding Oolong, Wenshan Baozhong, Oriental Beauty, Alishan Tea, Qingxin Oolong, Jin Xuan Tea, Lishan Tea, and Cuiyu Tea, among others.

Interested in trying oolong teas from different regions? Purchasing them one by one can be both expensive and challenging to find authentic options. Does that mean only those extremely knowledgeable about tea have a chance to buy and savor these classic oolong teas? We recommend exploring oolong teas through tea sampler to discover the ones that suit your taste.iTeaworld offers two great oolong tea collection packs. One is a more affordable oolong tea selection, and the other is a fresh oolong tea sampler, picked in 2023. Both collections contain 4 teas.

Oolong Tea Sampler: Da Hong Pao, Tie Guanyin, Minnan Shuixian, and Fenghuang Dancong.

New Oolong Tea Sampler: Da Hong Pao, Tie Guanyin, Zhangping Shuixian, and Fenghuang Dancong.

These four teas originate from the Northern Fujian, Southern Fujian, and Guangdong regions, allowing you to fully experience the flavors of oolong teas from different areas with just one box.

As oolong tea has spread and with advancements in technology, variations in processing techniques due to different origins and tea tree varieties have led to a diverse array of oolong tea styles. So, for those of you who love tea, what type of oolong tea do you prefer the most?

Connected with other tea lovers, join in Discord

What's the Differences between Minnan Shuixian and Minbei Shuixian?

As we all know, Shuixian tea has a long-standing reputation in the world of oolong tea. Upon closer examination, one can discover that Shuixian tea has many fine distinctions, mainly categorized into two major types: Minnan Shuixian and Minbei Shuixian. Let's explore the differences between Minnan Shuixian and Minbei Shuixian.

Differences between Minnan Shuixian and Minbei Shuixian

1. Origin

There is a clear geographical distinction between Minnan Shuixian and Minbei Shuixian. Minnan Shuixian is primarily produced in more than ten counties and cities in the southern part of Fujian province, where it is relatively abundant and commonly found in the market. Minbei Shuixian, on the other hand, originated in the northern part of Fujian, specifically in the Dahu Village of Shuiji Township, Jianyang County, over a century ago, and is currently primarily produced in Jianou and Jianyang counties.

Even for more finely processed loose leaf teas like Shuixian tea, the production methods can differ due to the tea's origin, even within the same province. Paying attention to the origin of tea leaves is essential if you want to purchase the best loose leaf tea.

2. Appearance

Minnan Shuixian and Minbei Shuixian also exhibit certain visual distinctions. Minnan Shuixian has tightly rolled leaves with a sandy green color and a soft, glossy sheen. Minbei Shuixian, while having an even appearance and a sandy green color overall, features dark green leaves with white speckles near the central stem, often referred to as "clear dragon head and frog belly." These visual differences between Minnan and Minbei Shuixian are quite apparent when compared side by side.

3. Infusion Color and Aroma

Minnan oolong tea is known for its high, long-lasting aroma, with a scent reminiscent of orchids. Its taste is sweet, mellow, and refreshing, and the tea liquor is bright yellow. The leaves are bright yellow, thick, and uniform. Even after multiple infusions, the aroma remains pronounced, and the sweet taste lingers. In contrast, Minbei oolong tea has a rich, orchid-like fragrance, a full-bodied taste with a lasting sweetness, and a vibrant red infusion color. The leaves are thick and soft, exhibiting a "three red, seven green" pattern. However, in terms of reinfusion endurance, Minbei Shuixian is slightly less robust than Minnan Shuixian.

Minnan Shuixian Representatives

1. Zhangping Shuixian

Zhangping Shuixian, like Yongchun Shuixian, draws inspiration from tea production techniques in both Minbei and Minnan, but it features a unique and innovative appearance. It is shaped like small square tea cakes and is the only tightly compressed tea in the world of oolong tea. Zhangping Shuixian has a traditional flavor with the richness and sweetness of rock tea, as well as the floral aroma of Tie Guanyin (Iron Goddess of Mercy).

2. Yongchun Shuixian

Yongchun County is one of Fujian province's three major export bases for oolong tea, with approximately 140,000 mu (about 9,333 hectares) of tea gardens in the county. There are currently 20,000 mu dedicated to Shuixian tea, distributed in towns and townships such as Huyang, Dongguan, and Dongping, with an annual production of 1,500 tons. Yongchun Shuixian initially followed the production methods of Minbei (North Fujian), but later incorporated the strengths of both Minbei and Minnan (South Fujian) techniques. This has made Yongchun Shuixian more resilient for steeping, with a fresher aroma and a bright yellow liquor. It combines the rich and long-lasting aroma of Minnan Shuixian with the mellow and smooth taste of Wuyi Shuixian.

iTeaworld offers a Minnan Shuixian produced in Yongchun County. The tea trees have a history of over 60 years, and the resulting tea leaves are highly durable for steeping, with a rich tea liquor and a clean, high aroma. It is definitely worth trying.

Minbei Shuixian Representatives

1. Wuyi Shuixian

Wuyi Mountain is renowned for producing loose leaf black tea and loose leaf oolong tea, with a greater variety of loose-leaf oolong teas. Concerning the oolong teas produced in Wuyi Mountain, there is a saying that goes, "No oolong is as mellow as Shuixian, no aroma surpasses cinnamon, and no rhyme is like Da Hong Pao (a famous oolong tea)." Wuyi Shuixian has a rich, fresh, and smooth taste that is both silky and sweet. It exudes an elegant and enduring high aroma, with a natural floral fragrance akin to orchids. Although its flavor may not be as rich as Da Hong Pao or as dominant as cinnamon, its unique water rhyme offers a distinct and enjoyable experience.

2. Jianyang Shuixian

Jianyang is situated in a high-mountain tea region, and different mountains impart unique "mountain rhymes" to its Shuixian tea. Jianyang Shuixian places a strong emphasis on "absorbing water," aiming to derive aroma from taste and emphasizing "activity." The liquor of Jianyang Shuixian is either orange-yellow or golden, with a clear appearance. It features a clear and enduring high aroma, while the tea leaves are thick, soft, and shiny, with red edges.

3. Jianou Shuixian

Jianou is the largest oolong tea export production base in Fujian, with Shuixian tea being the primary product and the largest Shuixian tea export production base in the country. The dry leaves of Jianou Shuixian are thick and robust, with a dark brown hue. After steeping, it exhibits a noticeable caramel aroma, and the tea liquor is orange with a hint of red. Its taste is full-bodied.

This article shares information about the differences in origin, appearance, infusion color, aroma, and processing between Minnan Shuixian and Minbei Shuixian, along with representative teas from each region. Hopefully, this information will be helpful when selecting and purchasing Shuixian tea in the future.