In China, tea is not always brewed with tea leaves alone. For centuries, people have added flowers, fruits, and even certain traditional herbs to tea to enhance aroma, depth, and mouthfeel, or to create a cooling or warming effect.

Common additions include chrysanthemum, dried tangerine peel (chenpi), red dates, and goji berries.

During winter, especially in southern China where cold and damp weather is common, boiling tea or steeping it in a thermal flask becomes part of daily life.

Because of its warming nature, chenpi naturally becomes a popular choice for winter tea drinking.

Is Chenpi the Same as Dried Orange Peel?

Not exactly. According to the 2020 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, chenpi refers specifically to the dried, mature peel of Citrus reticulata Blanco and its cultivated varieties, such as Chazhigan, Fugan, and Satsuma mandarin. After the fruit is peeled, the skins are sun-dried or gently dried at low temperatures, then aged in a natural environment with alternating humidity for at least three years.

Aging is the heart of chenpi. Over time, the volatile oils in the peel gradually decrease, while flavonoid compounds increase.

The aroma slowly shifts from fresh citrus notes to deeper layers of herbal, woody, and subtly sweet-and-tart scents, similar to dried plum.

On the palate, aged chenpi becomes smoother, more mellow, and gently sweet, with a long, lingering finish.

The sharp, spicy edge of fresh peel fades with age. The longer chenpi is aged, the more valuable it becomes.

By contrast, ordinary dried tangerine peel usually has a thin, flat aroma and a simple taste. Without proper aging, it is more prone to mold, and in some cases may even contain pesticide residues.

What Are the Benefits of Chenpi?

Chenpi from Xinhui, Guangdong is the most well-known and widely respected.

This region has a long cultivation history, a unique climate, traditional processing techniques, and the Chazhigan cultivar, all of which make it the core area for authentic chenpi.

Xinhui chenpi is known for its dense oil cells and higher concentrations of volatile oils and flavonoids.

Local farmers process fruit harvested at different stages of ripeness into distinct types of chenpi, each with its own character.

- Green Peel (Unripe Fruit)

Bold, spicy, and citrus-forward, with lower sugar content and minimal sweetness.

Traditionally valued for aiding digestion, relieving food stagnation, helping relieve constipation, and easing feelings of irritability.

- Semi-Ripe Peel (Erhongpi)

A balance of gentle spice and light sweetness.

It retains some of the brightness of green peel while developing a rounder, more mellow aroma.

The taste is cleaner, with less acidity and a soft sweetness.

Its effects are considered moderate, often associated with relieving heaviness, cough, and low mood.

- Fully Ripe Peel (Dahongpi)

Naturally sweeter, with a rich, sweet citrus aroma.

It brews beautifully on its own, offering a smooth, full-bodied taste with lasting sweetness and salivation.

Traditionally regarded as gentle and suitable for long-term drinking, supporting digestion and helping manage dampness.

- Post-Winter Solstice Peel

Harvested after the winter solstice, this type highlights sweetness even more.

The aroma is restrained yet deep, with pronounced aged notes and a long, powerful aftertaste.

It is often appreciated for its soothing qualities and is associated with lung care and skin nourishment.

Today, regions such as Pubei in Guangxi, as well as parts of Zhejiang and Sichuan, are emerging as new chenpi-producing areas due to favorable growing conditions.

How Chenpi Is Used in Daily Life

In southern China, chenpi is more than a tea ingredient.

It is commonly used in soups, stews, congee, and home-style cooking to support digestion and balance richness.

Traditionally, chenpi has been viewed as something both practical and worth storing long term.

Because it improves with age, it has been treasured for centuries.

It appeared in medicinal texts as early as the Song Dynasty, became a tribute item during the Ming and Qing dynasties, and in Guangdong, some families even store Xinhui chenpi as part of a daughter’s dowry.

What Does Chenpi Taste Like When Paired With Aged Tea?

Chenpi is often brewed not only on its own, but also with aged teas such as aged white tea, pu-erh, and dark tea.

These teas develop a smoother, richer body through aging, and chenpi adds bright citrus notes, gentle herbal aromas, and a refreshing lift that softens heaviness.

For first-time drinkers, the herbal intensity of chenpi may feel unfamiliar, but with time, the balance becomes easy to appreciate.

If you would like to try these 6 citrus teas, you can click the link to learn more>>

1. Chenpi + Pu-erh

Whether paired with aged raw pu-erh or ripe pu-erh, chenpi adds a subtle citrus and herbal layer without overpowering the tea itself.

Pu-erh’s deep, grounding character balances the peel’s aroma, creating a warming and comforting cup that feels especially pleasant after meals.

2. Chenpi + Liubao Tea

Chenpi helps soften Liubao’s earthy storage notes while adding a cleaner, brighter dimension. When steeped in a thermal flask, the prolonged heat creates a thick, full-bodied liquor. The spice of chenpi becomes gentle and calm, with a light citrus fragrance rising even before the first sip.

3. Chenpi + Aged White Tea (Shoumei, Gongmei)

This pairing feels very different from dark tea. Aged white tea is naturally sweet and smooth, yet slightly cooling in nature. Chenpi fills that gap with warmth and softness.

When simmered or steeped for a long time, the herbal and citrus notes become especially clear, with a silky, sweet finish.

4. Chenpi + Aged Oolong

This is a less common combination, but surprisingly harmonious.

The first impression is the rich herbal aroma of chenpi, followed by a thick, rounded tea liquor that fills the mouth. After swallowing, a gentle cooling sensation lingers, adding depth and contrast.

How to Tell Real Chenpi From Fake Ones

Because chenpi becomes more valuable with age, some sellers artificially age fresh peel to imitate old chenpi.

While professional testing is ideal, everyday drinkers can make a basic judgment by observing appearance, aroma, and taste.

1. Appearance

- Authentic chenpi has a rough surface with visible texture, often described as “boar bristle” patterns. The oil cells are full and raised, and the white pith naturally flakes off in a snow-like pattern. Color appears uneven, ranging from golden yellow in younger peels to amber tones in older ones.

- Fake chenpi tends to look flat and dark overall. The inner pith remains tight and intact, oil cells lie flat on the surface, and the color appears unnaturally uniform.

2. Aroma

- Younger chenpi shows clear citrus notes. With age, the fragrance shifts toward herbal and woody layers, becoming more complex.

- Artificial peels often smell sharp, perfumed, sour, or sweet in a single, unnatural way.

3. Taste

- Real chenpi starts slightly bitter, then turns sweet, with a bright golden liquor. Even after long steeping, the peel remains intact and resilient.

- Fake chenpi tastes flat or overly sweet, sometimes with a harsh edge. The peel is thin and fragile, breaking apart after just one or two brews.

4. Scraping the Oils

- When lightly scraped with a fingernail, real chenpi releases fine oil droplets and leaves a natural sheen. A subtle aged aroma lingers on the fingers. Younger peels show more visible oil, while older peels appear gentler and drier.

- Fake peels either release no oil at all or feel greasy and artificial. The scent fades quickly and lacks depth.

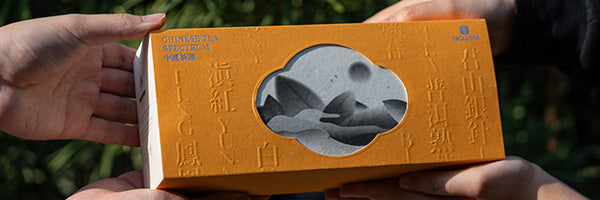

If you want to experience the true flavor of aged chenpi, try our Citrus Tea Sampler.

It includes five blends pairing aged chenpi with different teas, plus one pure chenpi that you can add to other teas as you like.

One box covers all your needs for exploring Chinese chenpi tea.